Early in September, Sudan and South Sudan were hit by sudden and massive floods, with the Blue Nile reaching water levels not seen for nearly a century.

The heavy rainfall claimed the lives of dozens of people, and affected at least 800,000 others in its wake. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has revealed that some 125,000 refugees and internally displaced people are among those affected.

Some canal banks and cultivated lands in Sudan, South Sudan, as well as Egypt were submerged by the flood waters, with the impact of the flooding reaching even as far as downstream governorates in Egypt’s Nile Delta region.

Some canal banks and cultivated lands in Sudan, South Sudan, as well as Egypt were submerged by the flood waters, with the impact of the flooding reaching even as far as downstream governorates in Egypt’s Nile Delta region.

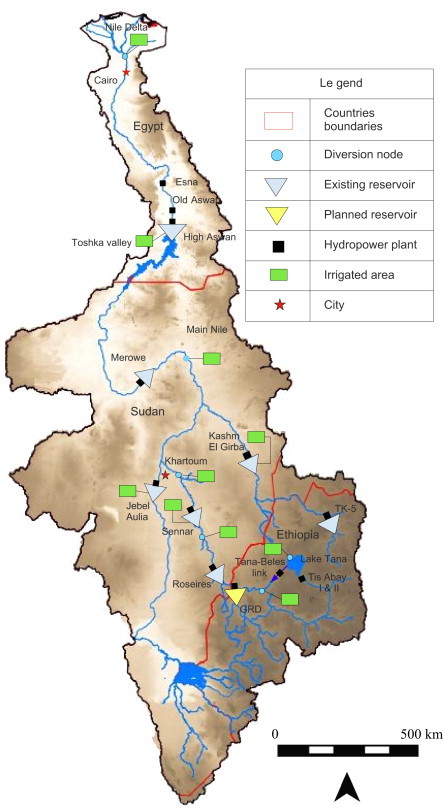

The Nile Basin is shared by about 400 million people in 11 countries, namely Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Egypt, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Eritrea, and Kenya. The economies of all these countries depend heavily on agriculture, with the sector employing the vast majority of the labour force in most of these countries.

Experts believe that the latest wave of floods is a warning of the climate change, which is threatening Nile Basin nations. With the region set to have a total population of 1 billion people by 2050, cooperation between Nile Basin countries has become a must.

Water Scarcity

Despite the huge amounts of water the Nile Basin receives every year, almost half of its countries are projected to live below the water scarcity level of 1,000 cubic metres (cbm) per person annually by 2030, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Egypt’s Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation Mohamed Abdel Aaty recently warned that climate change will negatively affect his country’s underground water stock in the Nile Delta.

He noted that Egypt is working on desalination projects to cope with the crisis, adding that “Egypt will become the largest consumer of reused water globally”. He also clarified that the budget that Egypt has allocated to its water projects now stands at $50bn.

The minister said that water per capita will decrease by 20% over the next decade to 500 cbm per year, which is lower than the international water per capita. This will affect people’s lives and negatively impact security and stability. Egypt is heavily reliant on its share of the River Nile’s waters, which provides the country with 97% of its water needs.

Any future changes in the volume of water flow coming from the River Nile can lead to significant impacts on the people living within the basin. It may also increase the already high level of water stress, according to a 2017 paper published in Nature Climate Change.

Based on a variety of global climate models and records of rainfall and flow rates over the last 50 years, researchers at MIT project a 50% increase in the amount of flow variation from the River Nile from year to year.

Based on a variety of global climate models and records of rainfall and flow rates over the last 50 years, researchers at MIT project a 50% increase in the amount of flow variation from the River Nile from year to year.

According to the paper, the warmer climate will increase the intensity and duration of the Pacific Ocean phenomenon known as the El Niño/La Niña cycle. This phenomenon had previously shown a strong connection to annual rainfall variations in the Ethiopian highlands and adjacent eastern Nile basins, from which 80% of the River Nile’s waters come.

Elfatih Eltahir, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the paper’s lead author, said that the study points to the importance of focusing on the potential impacts of climate change. Along with the rapid population growth, these form the most significant drivers of environmental change in the Nile Basin.

“We think that climate change is pointing to the need for more storage capacity in the future,” said Eltahir, referring to the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), “The real issues facing the Nile are bigger than that one controversy surrounding that dam.”

The paper’s findings suggest that there will be substantially fewer “normal” years, with flows of between 70 and 100 cbm/year. There will also be many more extreme years with flows greater than 100 cbm, and more years of drought.

More rain, less water

Another study agrees with Eltahir and his colleague’s projections on increased rainfall but less water.

In a paper published late in 2019 in the journal Earth’s Future, the researchers warned that by the end of this century, the frequency of hot and dry years may rise by a factor of 1.5 to 3, even if warming is limited to a global average of 2°C.

Despite the hopes that Ethiopia holds on its dam project, the researchers expect that its huge water reservoir will need five to 15 years to fill. At the same time, however, climate change is expected to make the river’s flow 50% more variable, increasing drought years and making the dam’s operation more challenging.

Egypt, the most dependent country on the River Nile for meeting its water demands, is expected to face a 25% drop in its water flows during the filling period.

However, climate projections estimate a 20% increase in rainfall in the Upper Nile basin by the end of the century. Researchers warn that more rainfall is not a good sign, but means more floods and a devastating frequency of hot and dry spells.

“By 2040, a hot and dry year could push over 45% of the people in the Nile Basin, or nearly 110 million people, into water scarcity,” researchers predict.

Professor Eltahir believes that countries in the Eastern Nile Basin should develop a common regional approach to incorporate the potential impacts of climate change on rainfall and river flow in any negotiated agreement.

Moreover, international water resources expert Adel Bahrawy warned of the impacts of climate change on the Nile Delta as sea level rises are accelerating. He added that cooperation is a must to save the lives of millions of people in the Nile Basin, and cope with the impacts of climate change on agriculture, water stress, and coastal zones.

“Now is the time for all 11 River Nile sharing nation-states and the international development community to pull together,” said Richard Paisley, Director of the International Waters Governance Initiative at the University of British Columbia in an article in the Conversation.

“They must redouble their efforts to successfully establish and maintain a Nile Basin wide cooperative framework agreement and a Nile Basin Commission,” he added, “These initiatives would clearly help focus the region on establishing a nascent international river basin organisation that could eventually embrace larger water and energy governance solutions.”

Professor Stephen Darby, from the UK’s University of Southampton, also stressed the need to manage rivers and deltas in a holistic manner.

He added that we need to mitigate and adapt to climate change, as well as to recognise that local pressures, such as pollution, water abstractions, sand mining, and pressures expressed in distant parts of the river catchment upstream may have more important impacts. He said that these causes need to be addressed.

Regional organisation, the Nile Basin Initiative, is actively warning of the socio-economic and environmental impacts of climate change on the Nile Basin countries.

Egypt’s cooperation efforts

Egypt’s Deputy Minister of Irrigation Ragab Abdel Azeem affirmed Egypt’s efforts to cooperate with other Nile Basin nations in various projects.

“Egypt is transferring its expertise in water management and groundwater use through the training centre of the ministry,” Abdel Azeem said, “It is also implementing projects to combat the Eichhornia plant in the River Nile in Rwanda, Burundi and Uganda.”

He added that these countries have suffered greatly from an overabundance of Eichhornia, the common water hyacinth that has become particularly invasive outside its native Amazon, and which has hindered the River Nile’s fish wealth.

Egypt has also helped some Nile Basin countries with flood protection works, such as the Kasese Dam project in Uganda.

Furthermore, Egypt’s Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation Mohamed Abdel Aaty said that his country is supporting Nile Basin countries in facing climate change and achieving sustainable development. He added that Cairo will shortly inaugurate a flood prediction centre in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s capital, Kinshasa, in early 2021.

Abdel Aaty said that Egypt is continuing cooperation with Nile Basin countries in the fields of: providing drinking water; harvesting rainwater; protection from the dangers of floods; livestock projects; and building capacity for technical professionals from Nile Basin countries.