Today on November 4, the 99th anniversary of the discovery of the King Tut Ankh Amun tomb, and looking very much forward to the opening of the restored Sphinx Avenue linking the Karnak and Luxor Temples, I would like to share with you yet another charm in the ancient Egyptian capital.

The Karnak Temple in Luxor overwhelms the visitors with its exceptional scale and historic value. I am one of those admirers of this world heritage. But for a diplomat coming from Japan, it was most striking to find its walls containing the inscriptions of the oldest peace treaty in the world, the treaty of Kadesh.

The Hittite version of this treaty is better known to some people. A replica of the clay tablet with cuneiform inscriptions is at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. It is regrettable that numberless travellers to Luxor do not notice this wonderful hieroglyphic version if they are more aware of the Battle of Kadesh. So, I decided to dig into this, with the help of Egyptian friends.

Two giant powers in the Middle East, the New Kingdom of Egypt under Ramesses II and the Hittite Empire under Muwatalli II went into a fierce battle at Kadesh on the Orontes River near today’s Homs, just some kilometres from the Syria-Lebanon border. This seemed to happen around 1274 BC, although there is still controversy about the exact time. A number of stone walls at Abydos, Karnak, Luxor and Abu Simbel describe the Egyptian version of the battle and the heroic victory of Ramesses II.

About 16 years after the battle, an official peace treaty was concluded between Ramesses II and Hattusili III, the new king of the Hittites, against the background of rising pressure from Assyrians and a succession race in Hittite. The hieroglyphic version of the treaty was engraved in the walls of the Ramesseum and the Temple of Karnak in Luxor.

Detailed accounts of the battle are exciting and valuable in military history. But it is even more meaningful for us today that the oldest peace treaty was agreed upon and visible for everyone.

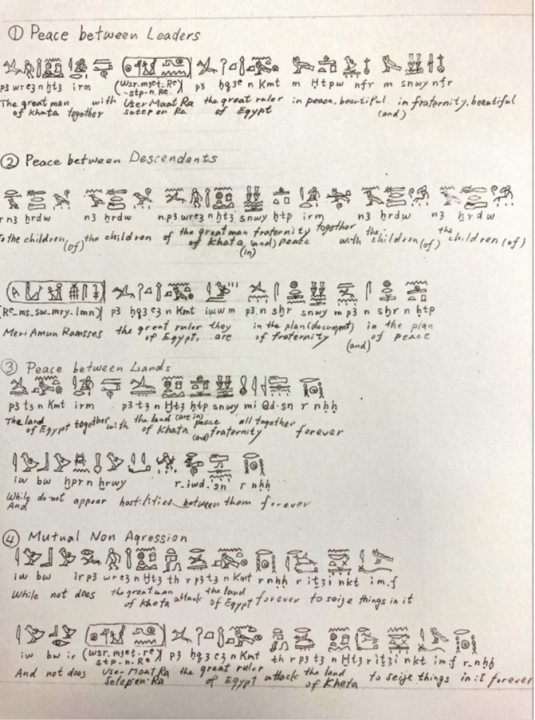

I may summarize the essence of their mutual commitments as follows:

1 There will be permanent peace and fraternity between Egypt and Hittite.

2 Neither side will violate the other’s land.

3 When one of them is attacked by a third country or internal forces, the other side will send its force to help.

4 Each side will send back dissidents and emigrants from the other side.

We can find here two characteristics, a peace treaty to end the war, and an alliance treaty to mutually commit non-aggression and assistance. It is surprising to find in such old days a proto-type of today’s legal mechanism for peace and security.

When I visited the Karnak Temple, I found the treaty text on the wall extending south of the Great Hypostyle Hall, after imposing scenes caved in reliefs together with texts on battles against the enemies. Unfortunately, the people who lived here afterwards, used the walls to sharpen the knives, and some inscriptions are eroded, but the main parts of the text are readable.

It is beyond my capacity to read all of them, but I wanted to check the fundamental part of this treaty, a promise of peace between the two empires. The text in question was located more than 3 meters high and I could not see it. So, I asked for help from Dr Mustafa Waziri, Secretary-General of the Supreme Council of Archaeology. He kindly allowed me to use ladders in front of the wall so I could see the texts and take their photos. There were some illegible parts, but I was excited to identify a sentence which means “(the land of Kemet (Egypt)) together with the land of Kheta (Hittite) (will be in) peace and fraternity all together forever and hostilities will never happen between them, forever.”

I took time to write and understand word by word the two lines relating to the promise of eternal peace. I have to thank excellent Egyptologists who helped me in this, such as Dr Zahi Hawass, Dr Tarek Tawfik, and Dr Ola El-Aguizy, who generously answered my strange questions. My handwriting of the texts became a good souvenir of Egypt.

Hieroglyphs is said to be very peculiar because it uses both ideogram and phonogram (Jean-François Champollion discovered the phonogramic use of hieroglyphs in 1822, using the cartouches of Ptolemy and Kleopatra on the Rosetta Stone), but it is the same with Japanese. We use KANJI (ideogram) and KANA (phonogram). I even felt familiar with hieroglyphs.

There are already many studies by experts on the treaty, but I found particularly interesting the method to realize eternal peace.

It goes in three steps.

Eternal peace and fraternity were promised, first, by the two leaders, Ramesses II and Hattusili III, then, by their children, or people, and, finally, by the two lands, or countries, Egypt and Hittite.

The international relations at that time depended on personal relations between sovereigns and the relations would change when kings change. But Kadesh Treaty turns a personal promise between leaders into an agreement between countries. Here we find the basic principle of today’s international law: agreements between states must be respected even if the leaders or governments change. Of course, this is not always the case in realpolitik

There were also interesting findings in the language.

The text uses the throne name of Ramesses II (“User Maat Ra, Setep en Ra” meaning “the justice of Ra is powerful, chosen of Ra.”). Usually, this name is forwarded by the title of “Lord of upper and lower Egypt” (Neswt biti) to stress the authority to unify the territories. But in this text, the title is “Great ruler of Egypt (Heqa aA en Kemet),” maybe because it was more crucial for the pharaoh to represent the whole country.

Here the “ruler” is expressed by the symbol of divine authority, Heka sceptre, or the pharaoh’s shepherd’s stick. But his counterpart, Hittite King is shown by a standing person. He was at most “a great man.”

There is a similar asymmetry when narrating the peace between the children. In hieroglyphs, children are expressed by combining letters to give the phonetics and a sign, called “determinative,” to give the meaning. For Egyptians, the determinative is a sign of a child, but for Hittites, it is a sparrow, meaning small or weak. A bit pejorative.

These are examples of translation techniques in ideogramic languages. Without necessarily changing the meaning, it is possible to glorify oneself and trivialize others. There were similar exercises in ancient Asia, using Chinese characters, for example, when designating “barbarians.”

By studying only two lines on the wall of the Karnak Temple, I learned a lot of things. But here is the most important lesson. The battle of Kadesh was not only a glorious page in Egyptian history. Its peace treaty was a milestone in world history and continues to send us a message for international peace from Egypt 3300 years ago.

NOKE Masaki is the Japanese Ambassador in Egypt

Note: This article is a personal opinion and does not express the opinion/position of the Government or the Embassy of Japan