Twenty-four countries signed an agreement banning the use of harmful and ozone-depleting substances such as chlorofluorocarbons on 16 September 1987. This protocol was known as the “Montreal Protocol” in reference to the Canadian city that embraced the agreement, which has been approved by more than 190 countries so far.

More than four decades after the signing of the Montreal Protocol, scientists expect the ozone layer to recover in another four decades from now, with global efforts to phase out ozone-depleting chemicals accelerating as a corollary to mitigation efforts to climate change and global warming.

Earth shield

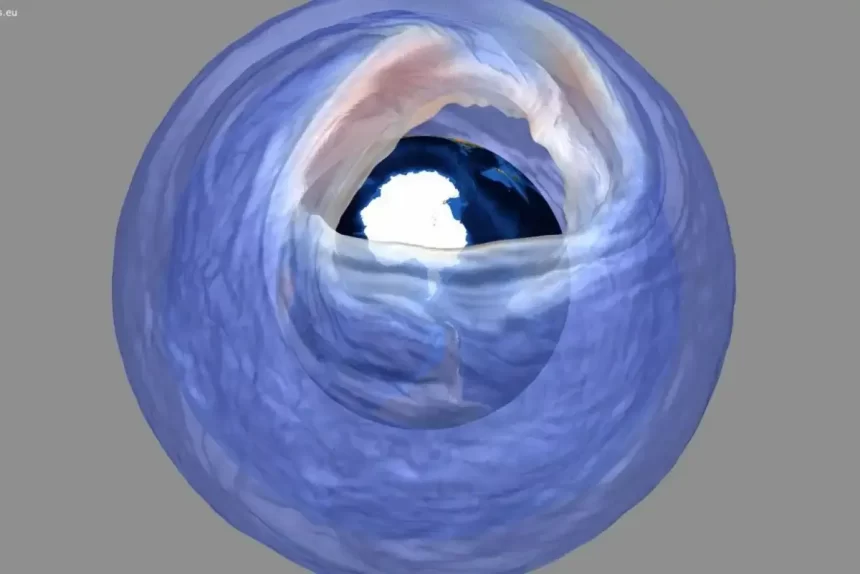

The ozone layer is the part of the stratosphere that protects our planet from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. It is a zone of the upper atmosphere, roughly between 15 and 35 kilometers above the Earth’s surface that contains relatively high concentrations of ozone (O3) molecules. Almost 90 percent of the ozone in the atmosphere is found in the stratosphere, which is the region from 10 to 18 km to nearly 50 km above the Earth’s surface.

The temperature of the atmosphere in the stratosphere is increasingly rising, a phenomenon caused by the ozone layer’s absorption of solar radiation. The ozone layer effectively blocks almost all solar radiation of wavelengths less than 290 nanometers from reaching the Earth’s surface, including certain types of ultraviolet light and other forms of radiation that can injure or kill most living organisms.

Scientists believe that the formation of the ozone layer played an important role in the development of life on Earth by filtering out lethal levels of ultraviolet radiation, thus facilitating the migration of life forms from the oceans to land, according to molecular biology theories.

In the quartet report prepared by the UN-backed panel of experts, which was presented on 9th of January at the 103rd annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society, experts warned that some “unintended” impacts could have negative consequences for Earth’s radiation shield. harmful.

By unintended effects, scientists are referring to measures being used by some countries known as “geoengineering” that add aerosols to the stratosphere as a possible way to reduce global warming by increasing the reflection of sunlight. But the report warns that unintended consequences of stratospheric aerosol injection could also affect stratospheric temperatures, the stratospheric cycle and ozone production, ozone destruction and transport rates.

The report includes the results of the evaluation that takes place every four years to follow up on the extent of the countries signatories to the Montreal Protocol’s commitment to the terms of the agreement, which aims to reduce greenhouse gases that cause the depletion of the ozone layer that protects life on Earth, and can be described as the “Earth Shield”.

This year’s outcome indicated that adherence to the terms of the agreement resulted in the phase-out of nearly 99% of banned ozone-depleting substances, resulting in a marked restoration of the upper stratospheric ozone layer and a reduction in human exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

Kigali amendment

In January 2019, the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol took effect, taking an important step on the path to reducing the production and consumption of powerful greenhouse gases known as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and significantly limiting global warming. HFCs are organic compounds frequently used as refrigerants in air conditioners and other appliances as alternatives to ozone-depleting substances controlled under the Montreal Protocol.

Chlorine compounds, including trichlorofluoromethane, are among the compounds that deplete the ozone layer, which the Montreal Agreement stipulates seeking to protect and reduce its depleting emissions. The recovery of the ozone layer depends on the continued decline in trichlorofluoromethane concentrations.

The amendment, which is three years overdue (it was signed in 2016), requires a gradual reduction in the production and consumption of certain hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). HFCs do not directly deplete ozone, but rather are powerful gases that cause climate change.

The United Nations expects that, if adhered to, the Kigali Amendment will reduce up to 0.4°C of global warming over the current century, while still protecting the ozone layer and achieving the Paris climate agreement’s goals of keeping global temperature rises below 2°C. .

And in September of 2019, the European Union’s Earth Observation Program “Copernicus” announced that the ozone hole was likely to have reached its smallest size in 2019 compared to the past 30 years, reaching a size not exceeding 10 million square kilometers compared to 25 million square kilometres at the height of decline. The Observatory attributed this progress to the parties’ success in implementing the Montreal Protocol.

Signals from Antarctica

The new UN report says that if countries continue to abide by the provisions of the Montreal Protocol, the ozone layer is expected to return to levels before the ozone hole appeared in 1980, by 2066 over the Antarctic, by 2045 over the North Pole, and by 2040. to the rest of the world.

A study published by the US Space Agency “NASA” on 27 October 2022 showed a decrease in the size of the ozone hole above the South Pole, to reach 23.2 million square kilometers between 7 September and 13 October 2022. This area of depletion of the ozone layer over Antarctica was slightly smaller than Last year and in general the hole in general has continued to shrink in recent years.

The researchers noted some fluctuation in the size of the hole with changing weather conditions and other factors that make the numbers fluctuate slightly from day to day and week to week.

On 15 December 2022, experts at the Copernicus service, when the Antarctic ozone hole closed in 2022, detected some unusual behaviour. Not only did the ozone hole take longer than usual to close, but it was a relatively long time, and different from what has been observed in the past 40 years.

The Antarctic ozone hole usually begins to widen during the Southern Hemisphere spring (in late September) and begins to shrink during October, before closing completely in November, as is usual. However, the efficiency management system data from the past three years show a different behaviour.

Regarding the reasons for this new behaviour, European experts said – according to the report issued by Copernicus- that there are several factors that influence the extent and duration of the ozone hole each year, in particular the strength of the polar vortex and temperatures in the stratosphere. The past three years were also characterized by strong eddies and low temperatures, resulting in cascading large and prolonged ozone hole episodes. They also suggested a possible relationship with climate change, which tends to be stratospheric cooling.

But despite the report’s extraordinary results, European experts praise the provisions of the Montreal Protocol, thanks to which they say concentrations of ozone-depleting substances have been decreasing slowly but steadily since the late 1990s. The ozone-depleting substances concentrations in the stratosphere are expected to return to pre-industrial levels within 50 years.