BAGHDAD: The leaders of two rival political alliances battling to run Iraq’s new government took a step toward ending their power dispute Saturday, as the Sunni-backed coalition that won March elections now faces being sidelined in parliament.

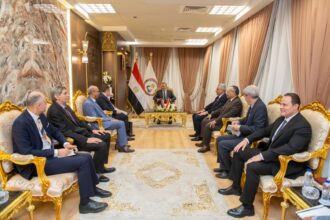

The 90-minute meeting between Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki and former Premier Ayad Allawi was their first since the March 7 vote, and was described by aides as more of an icebreaker than the start of serious negotiations.

The secular but Sunni-dominated Iraqiya coalition that Allawi heads risks losing a grasp on its narrow electoral triumph due to infighting and outmaneuvering by Al-Maliki and his fellow Shia rivals.

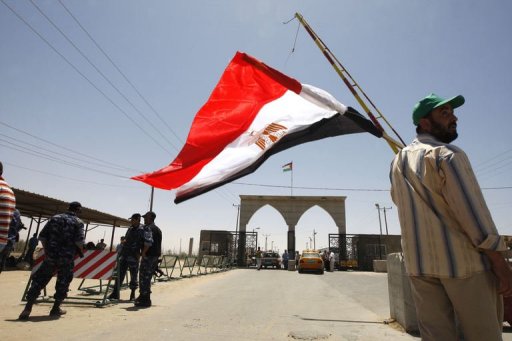

As the new legislature convenes Monday, that prospect is serving as a lesson in Iraq’s nascent democracy, where rules can bend. It also, more ominously, raises the possibility of a revitalized insurgency if Sunnis conclude that they have no place in government as US troops pull out of Iraq.

"That’s why it’s important to have a unity government," Army Gen. Ray Odierno, top US commander in Iraq, told a Pentagon news conference last week. "We don’t want to see any group that feels it’s been disenfranchised and even contemplates moving back to an insurgency."

Iraqiya alliance is struggling to capture key government posts — a task that should have been all but certain after it took more than a quarter of parliament’s 325 seats in the vote.

Iraqiya won 91 seats, two more than its closest rival. But Allawi, a secular Shia, has little if any chance to reclaim the prime minister’s job he held in 2004-05, and risks top Cabinet positions for Sunni allies if he insists on it, according to Iraqi officials close to ongoing negotiations.

Iraqiya "might have no postelection role," Hassan Al-Alawi, a senior Iraqiya leader, said in an interview with The Associated Press. "They are walking a dangerous route."

He added: "Allawi will never be the PM."

Iraqiya’s victory was initially heralded as a groundbreaking step toward a secular Iraqi government after years of Sunni-Shia tensions that brought the country to the brink of civil war in 2005-07. For many in the West, it was a soothing outcome in the face of a US military drawdown that will send home about 45,000 American troops this summer and leave security in the largely untested hands of Iraqi army and police forces.

But a back-room deal between two major Shia coalitions, brokered with the help of Iran, birthed a new bloc, the National Alliance, aimed at wresting power from Iraqiya and dominating parliament with a combined 159 seats. Al-Maliki leads the new bloc’s two or three top contenders to run the majority Shia country.

A March court opinion open the question of whether parliament’s largest power bloc is one decided by the vote or created after the election. Iraqiya and the National Alliance are each expected to claim it is the largest, setting up a fight that could last for weeks if not months.

In an opinion piece published Thursday in The Washington Post, Allawi accused Al-Maliki of defying "the will of the people" by building the new alliance to amass power. Al-Maliki "refuses to acknowledge his defeat or Iraqis’ clear desire for change and national progress," Allawi wrote.

But internal divisions have also bedeviled Iraqiya.

Iraqiya’s top Sunni members are frustrated that Allawi has staked his claim on the prime minister’s job, potentially at their cost, according to Iraqi officials involved in the ongoing power-brokering negotiations. One person close to the negotiations said Allawi may also be willing to take the presidency, a largely ceremonial but untested post, clearing the way for Al-Maliki to remain prime minister. But that still would leave Sunnis without any of the top three government leadership positions, assuming one goes to a Kurd.

"I told Allawi that when you go on the platform, before the camera, make some balance for the figures around you," said Al-Alawi, a Shia.

Several Sunni leaders are either angling for an internal coup or threatening to leave Iraqiya — along with their supporters — if Sunnis do not obtain promises of high-ranking posts, according to the negotiators who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the private negotiations more candidly.

The infighting also reflects frustration over changing rules that put Iraqiya at a disadvantage even after winning the vote, said Stephanie Sanok, an Iraq expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

"Allawi and Co. did a very good job of involving voters who had not voted in the past," Sanok said. "They are severely disappointed in this outcome."

Following the 2003 fall of Saddam Hussein, Sunnis who once ruled Iraq were sidelined in the nation’s government and politics. That fueled the Sunni insurgency, leading to years of sectarian warfare.

Ambassador Gary Grappo, the political director at the US Embassy in Baghdad, said Iraqiya’s 91 seats still give it considerable sway in parliament, even if it is not declared the largest alliance. But he said Iraqiya must decide on which government posts for which to fight.

"Whether it’s the prime minister or something else, or a bunch of somethings else and no prime minister, these are the things they have to weigh and weigh carefully," Grappo said. "I would say, however, that they have a strong hand to play and it’s just a question of how well they play it." –Qassim Abdul-Zahra and Rebecca Santana contributed to this report.