Among the social and political effects of the rise of the post-revolutionary Islamic elite in Egypt is a harmful blurring between the civil and religious spheres. The two realms were often conflated in Egypt long before the revolution but this trend has been continued even further by Islamist forces in the past year-and-a-half.

Among the social and political effects of the rise of the post-revolutionary Islamic elite in Egypt is a harmful blurring between the civil and religious spheres. The two realms were often conflated in Egypt long before the revolution but this trend has been continued even further by Islamist forces in the past year-and-a-half.

The start of the current post-revolution incursion into the civil sphere by religious elements was the constitutional referendum in March 2011, where Islamist forces (mainly the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists) mobilised for a “yes” vote on a religious platform. From that point on, Islamist political forces kept a place for religious matters in all civil procedures. Mobilisation on religious grounds was repeated in the parliamentary elections, the Shura council elections and the presidential election. In urban and rural cities of Egypt, mosques were used by political parties as places for electoral rallying. Satellite channels, newspapers, youth centers and even public transportation were all used as platforms to insert religious discourse into civil matters. The result of that was a state of religious polarisation, Islamist domination over elected institutions and recurring religious presence in civil contexts.

A similar procedure of confounding the civil and the religious is taking place now. Since the beginning of Ramadan, Mohamed Morsy has been praying in a different mosque each night, something akin to a presidential prayer tour. It is indeed the right of every Egyptian individual to practice his or her religion in the manner they please. It is also understandable to be present in the mosque every night during Ramadan, a month where even non-practising Muslims become pious. What strikes me as unusual is the giving of speeches or making statements about politics during prayer time. Over the past week, I have read at least three statements made by Morsy in a mosque. The problem is not with a president who goes to the mosque to pray, the problem is with combining religious and civil contexts. Morsy using a religious space to address political issues and exercising his civil position as president in a non-civil context is problematic.

Tellingly, the first interview I saw with the new prime minister also took place inside a mosque. The pictured interview on Al youm al sabe’ website shows the new prime minister answering questions from a chair in a mosque. The same issue arises with the prime minister as well, not with religion or piety, but with the fact that the already thin line dividing between the “civil” and the “religious” in Egypt is growing even thinner.

Those who fear the further incursion of religion into civil affairs should direct their attention to the constitutional drafting committee. Amidst the numerous problems facing Egypt today and the efforts to mobilise for different causes, the constitution remains the battle un-fought. The constitutional separation between “civil” and “religious” does not end with leaving the second article untouched, it rather extends to constitutional guarantees of civil liberties, basic freedoms and universal human rights. Non-religious political forces are faced with a challenge to coordinate efforts and visions on rights and freedoms in the new constitution. Otherwise, we will all be caught off-guard in an Islamic public sphere.

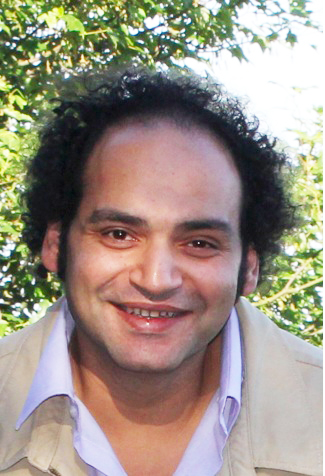

Ziad Akl is a political sociologist and a Middle East specialist at the Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies.

He is a senior researcher at the Egyptian Studies Unit and managing editor of the periodical “Egyptian Affairs.”