By Ines Bel Aiba (AFP) – Egypt, led by an Islamist ideologically close to the Hamas movement ruling Gaza, has recalled its ambassador from Israel and begun a flurry of contacts aimed at ending Israeli raids on the Palestinian territory.

But Cairo nevertheless finds itself in a delicate position.

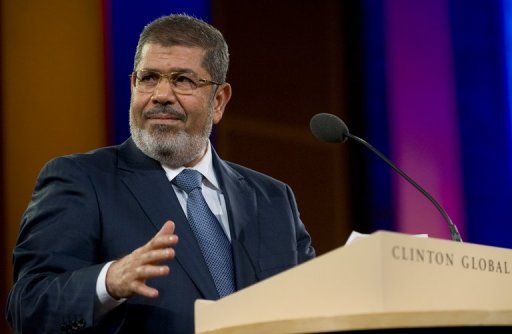

“The Israelis must understand that we do not accept this aggression, which can only lead to instability in the region,” President Mohamed Morsy said Thursday, as Israeli warplanes pounded Gaza and militants responded with rockets.

Morsy, formerly of the Muslim Brotherhood from which Hamas also sprang, on Wednesday recalled Cairo’s envoy to the Jewish state and also conferred on the crisis with US President Barack Obama and UN chief Ban Ki-moon.

He also urged the Cairo-based Arab League to convene an emergency meeting of Arab foreign ministers, which has been set for Saturday.

Morsy’s spokesman Yasser Ali told state television Prime Minister Hisham Qandil will travel to Gaza on Friday “to express our support for the Palestinian people and to see what they need.”

He will be accompanied by a number of Morsy aides and Health Minister Mohamed Mustafa Hamed.

The ruling authorities in Egypt find themselves torn between sympathy for the Palestinian cause and the need to preserve relations with Washington and maintaining the image of a responsible state.

“Shortly before dawn, I called President Obama and we discussed the need to put an end to this aggression and to ensure it does not happen again,” Morsi said on Thursday.

“I explained Egypt’s role, Egypt’s position, that we have relations with the United States and the world, but at the same time we totally reject this aggression.”

The two leaders agreed to continue “to communicate… to prevent an escalation,” Morsy added.

Essam al-Erian, deputy leader of Morsy’s Freedom and Justice Party (FJP), wrote on his Twitter account: “Egypt has changed. Its will has been liberated.”

The FJP warned that Cairo “will no longer allow Palestinians to be the objects of Israeli aggression as in the past,” and the powerful Muslim Brotherhood called for demonstrations on Thursday and Friday.

According to Mustafa Kamel al-Sayyed, professor of political science at Cairo University, the recall of Egypt’s ambassador does not just indicate that Cairo’s policy towards Israel has changed.

“What has changed is the rapid response. Before, it took time and came only after pressure was exerted,” Sayyed said, putting Cairo’s speedy reaction down to the close ties between the Brotherhood and Hamas.

The contacts between Morsi and Obama highlight concerns about maintaining a certain continuity, he added.

However Sayyed ruled out any unconditional reopening of Egypt’s Rafah border crossing with Gaza over “fears among security officials of terrorist elements crossing” from the enclave, as Cairo itself battles militants in the Sinai.

Egypt has relaxed entry conditions for Gazans since Morsy came to power, but has not lifted restrictions completely.

Morsy’s predecessor Hosni Mubarak, who stood down in February 2011 after a popular revolt, was seen as a moderate leader by the West but accused at home of being too complacent towards Israel.

Mubarak too ordered the recall of Egypt’s ambassador in 2000 after the second intifada, or uprising, but he was also a regular partner in peace talks between Palestinians and the Israelis, and met Israeli leaders several times.

Egypt was the first Arab country to sign a peace agreement with Israel, in 1979, and has frequently acted as an intermediary between Israel and Hamas.

Morsy, elected president in June this year, has promised a harsher stance towards Israel than his predecessor, but without challenging in principle the peace accord between the two nations.

In his speeches, however, Morsy never mentions Israel by name.