In “Railroads in the Land of the Nile”, Amr Nasr El-Din of the Economic and Business History Research Centre at the American University in Cairo recounts the history and development of Egypt’s railways. Seeking to reinforce their political and economic power in their colonies in Asia, the British and other European colonisers chose to use the new Middle East land and sea routes as an alternative to the sea route of the Cape of Good Hope. The Middle East land route passed through Egypt. At that time, Egypt owned two naval hubs; Alexandria and Suez.

Supported by new technologies introduced to Egypt by Mohammed Ali in the 19th century, the British thought of establishing a “land link” between Alexandria and Suez. After proposing the idea of a railroad to the Egyptian government, the project started in 1834 to connect Cairo and Suez. Shortly after Mohammed Ali stopped the project for fear increasing British intervention in Egyptian affairs, but under his successor, Abbas Helmy I, the project was resumed with a route from Alexandria to Cairo and from Cairo to Suez in 1851.

According to Nasr El-Din, frantic development of railroads in Egypt took place from 1858 till 1876, “surpassing expansions in the Egyptian railroad network throughout its 150 years of history”. Lines connected cities such as Tanta, Samanoud, Damietta, Zagazig, Ismailiya, Mansoura and Desouk. Modern day Egyptian railways owe much of its current network to that time.

Owning the first railway system in Africa, Egypt’s railway history has been a source of pride. However, its modern history in the past 10 to 20 years has been tainted with corruption, lack of maintenance and shed blood.

In November 2012, a train in the Upper Egyptian governorate of Assuit collided with a school bus leaving 48 dead; 44 of them were children.

On the eve of 15 January 2013, another collision took place at Al Badrashin in Giza, resulting in 18 deaths and 150 casualties; all were conscripts in the army.

These two recent accidents are not the worst in Egypt’s history; the worst dates back to 2002 with the Al-Ayyat train accident which took the lives of 361 victims. However, they were among the gravest and most painful coming after the 25 January uprisings that demanded human dignity and after electing President Mohamed Morsi who promised to deliver that demand.

According to the state-run Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics from October to December 2012 there were 130 accidents, compared to about 94 accidents in the same months of the preceding year.

The number of accidents in 2013 is still unclear. However, with the Al Badrashin incident at the beginning of the year and the train drivers organising their biggest strike in decades last April, all indicators reveal a looming crisis in the Egyptian national railways.

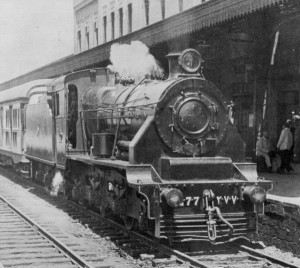

(Photo by : Amr Nabil)

What causes accidents?

“The primary reason for accidents is people’s behaviour,” says Yahia Shamalah, chairman of the Central Administration of Railway Engineering.

He explains that there are two types of railroad track crossings. The first one is the formal crossing constructed and overseen by the Egyptian Railway Authority (ERA). The second is an illegally built crossing by citizens residing in rural areas, where the railway lines pass, to facilitate passage of their carts or cars. According to the Central Administration of Railway Engineering, the number of formal crossings is 1,332 while the illegally built ones number around 4,000. Unsurprisingly, the illegal crossings are not subject to ERA regulations or supervision, thus these illegal crossings are more prone to accidents due to their poor construction and lack of oversight.

Shamalah says: “People build these crossings and pass over with no heed. Citizens do not follow instructions while crossing railway lines.”

He continues: “These [illegal crossings] are like landmines along railway lines. They are often the cause of daily collisions that happen between trains and cars, leaving us with casualties and victims.

“The problem is that media reports don’t differentiate between a formal crossing and an illegal one. ERA can’t build walls to demarcate railways all over Egypt. We only do that inside cities and communities. Sometimes we build a wall, people demolish it and make a crossing, in such case what can ERA do?”

When ERA finds out about one of these crossings, they report it to the police, but no further action can be made due to the proliferated number of illegal crossings.

Another issue is switchers, metal nails and steel along the railway line are often disassemble and stolen, costing the authority EGP 38m in losses for the year 2012 and also leading to accidents and derailments.

Mohamed Abdel Sattar is the president of an independent railway workers syndicate. He disagrees with Shamalah.

“The main reasons for persisting train accidents are three things: First, is financial and administrative corruption in ERA before and after the revolution. Second, labourers lack proper training from ERA for them to properly perform their duties. Third, the misallocation of resources leading to a lack of regular maintenance services,” Abdel Sattar explains.

When asked about maintenance, Shamalah emphasised this as a large part of the problem. He admits that the maintenance dedicated to passenger carriages, freight wagons, locomotives and railway lines, is of low quality. “The maintenance companies face many issues because there is a shortage in spare parts, 99% of which are imported with foreign currency,” he says.

(Photo by :Mohamed Omar)

Corruption in ERA

“Since 2005 we have been submitting reports to the prosecutor general about the corruption we witness inside ERA. Back then we (workers) were a pain to the people at the top. Now we are working through our independent syndicate, but we still see the same corrupt practices persisting,” says Abdel Sattar.

The Egyptian Centre for Economic and Social Rights published a report last January blaming accidents on the corruption of ERA. The report showed that the railway authority receives a huge budget that reaches 1.7% of the budget specified for the Ministry of Health; however its performance in developing the railways is almost nonexistent.

Last February, the state-owned Al-Ahram published an investigation into corruption taking place in the passenger carriages bid the ERA holds. The investigation showed laxity in the way ERA supervises such bids, which was demonstrated by the carriages’ incompatibility to standards mentioned in the contract between ERA and the importing company.

Corruption also takes place in maintenance companies with which ERA is collaborating. Airmass is a corporation that carries out maintenance for passenger carriages, freight wagons and locomotives, while there is another company that repairs railway lines. According to Abdel Sattar both companies do not perform their jobs properly leaving Egypt’s trains in hazardous conditions.

“In 2010, the former president of Airmass was arrested for the biggest corruption case in the history of Egyptian railways. He stole about EGP 800m. With a new leadership after the revolution, you’d expect the situation to get better, but the same corrupt legacy is continuing at different proportions,” he says.

Shamalah thinks the problem is solely financial.

“These companies get their budget from ERA and the authority is currently experiencing a significant financial deficit. ERA should specify ticket prices to increase profit margins [to cover costs like wages, salaries and maintenance]; however the government intervenes in the way ERA operates and imposes a specific lower price for train tickets.

“I think if the government subsidises tickets then the Ministry of Transportation should pump money into ERA’s budget to compensate for losses. The authority needs about EGP 1.2bn from the Ministry of Transportation and last year all it got was EGP 300m,” he says.

(AFP Photo / Stringer )

Misallocation of resources

Abdel Sattar says his duties at the railway workers syndicate have enabled him to witness the misallocation of resources that is carried out by ERA.

“Each railway station in Cairo and Alexandria costs about EGP 210m, shouldn’t this money be spent on maintenance?” he asks. “Instead of developing a queue, how about renovating carriages and locomotives that will preserve the lives of the passengers? However, that doesn’t happen at ERA because there is no vision.”

Cairo’s newly renovated railway station is truly a source of pride for Egyptians. It is internally decorated with embellishments that reflect Pharaonic, Coptic and Islamic civilisations. At the centre of state is a glass pyramid hanging from the ceiling upside down resembling the pyramid inside the Louvre in Paris. Outside the station two historic locomotives are parked on the left and right sides of the station offering it a classic character. However, the cost of the beautiful design was uncalled for in Abdel Sattar’s opinion.

Shamalah disagreed: “ERA’s resources should be spent on all aspects including having a presentable and exuberant train station for Egypt. The station will soon open shops, malls and restaurants that will bring in profits for the authority, same thing goes for Sidi Gaber station [in Alexandria]. Our station in Cairo was not on par with its counterparts elsewhere in the world, which is why we had to refurbish the station’s buildings.”

According to Shamalah the ticket price from 2005 up until now has not changed.

“Does it make sense to sell the student ticket for EGP 12 to use for nine months on a daily basis? The so-called ‘resources’ that come to ERA are really nothing, so how could the authority upgrade its services?” he wonders.

For the past month ERA and the Ministry of Transportation has been meeting with the World Bank to secure a loan to develop parts of Egypt’s railways. “Currently, we’re seeking loans from the World Bank and Kuwaiti Development Fund to implement our projects to upgrade electronic lights and renovating railway lines,” says Shamalah.

Since 2008 ERA has been working on a plan to develop 245 crossings; 171 of them will be equipped with electronic lights. ERA has been designing five-year and 20-year plans to develop railways, but with changes in leadership and lack of financial resources, these plans have yet to be into effect.

Abdel Sattar on the other hand believes the money coming into ERA is being wasted by top managers and other unnecessary expenditures.

Challenges and future prospects

“People still consider trains to be the safest means of travelling, all our trains are fully booked and some lines are filled three weeks in advance. Public turnout is as high as ever,” says Shamalah.

However, some passengers do not share Shamalah’s sentiments due to the current waves of roads and railway lines being cut by protests and demonstrations, causing the railways to acquire a notorious reputation.

Sabreen is a student from Aswan studying in Cairo. She says she does not feel safe on trains anymore due to railroad blockages. “Sometimes I take the bus, but they are even worse. I also travel by plane, but not as frequently because it’s too expensive and I can’t always afford it. I wish everything were better, especially cleanliness and train schedules. I wish the wave of accidents that take place due to negligence ends because it’s really frustrating.”

Elham Fadaly is a frequent traveler from Cairo to Beni Suef in Upper Egypt. She too has been affected by the deteriorating railway lines.

“Trains used to be the safest means of transportation for me from Cairo to Beni Suef. Now it is not the same at all. In the past, it took me three hours maximum to reach my destination, now I take at least four or five hours. I stopped taking trains six months ago, I use either buses or private car,” she says.

Like Sabreen, Fadaly wishes the trains were committed to their arrival and departure schedules, and that broken windows of the passenger carriages were replaced. “I wish to have my right to sit in my seat because crowds sometimes prevent me from reaching my seat and I end up standing for hours. I wish trains were cleaner and more humane,” she comments.

Ahmed Ezz, 22, is originally from Alexandria, but works at a company in Cairo. He travels to Alexandria to visit family. However, due to blocking railways, he was not able to travel to Alexandria for the Sham El-Nessim holiday.

“The line was cut; that’s always the case. The railway system is horrible; timings are bad, no air-conditioning most of the time, dirty and crowded carriages. The service is deteriorating everyday. It’s not worth the money,” says Ezz.

Cutting the railway lines and blocking trains have detrimentally affected the Egyptian railway system across all governorates. When a railway line is blocked, the trains’ schedule on that line is disrupted, passengers return their tickets and get refunds, and passengers on the blocked train could even clash with those blocking its way.

According to Shamalah when a blockage occurs, the average daily loss is around EGP 2m.

“In order to get the system back in shape, we need about 48 hours. That’s why we need our police to be more cooperative and to work properly on securing railway routes,” he explains.

Shamalah insists that financial solutions and additional funds pumped in from the government would be more helpful than anything else in developing Egypt’s railway system. “We need the government to help as much as it subsidises tickets. Then we definitely need to prioritise what to do with that money. We need to be focusing on improving the infrastructure of the railway system,” he notes.

Abdel Sattar chooses a difference approach.

“To go anywhere from the dangerous situation we’re in at the moment, we need to cleanse the institution from all corrupt heads. And they are known. Then we move to the issue of maintenance because without it the system is on the verge of collapse at any moment.”