By Rana Yazigi, Executive Director of Ettijahat Independent Culture

Cultural policies are essentially managed, or at least approved, by governments. Governments are the entities legally entitled to make decisions on the development of organisational structures and institutions, promote centralisation or decentralisation, and decide whether to raise the level of transparency and good governance or to monopolise decision-making and information. Governments are also responsible for enacting laws, developing national budgets and choosing the amounts that should be allocated to different sectors; governments determine a country’s cultural policies. What good would it do independent stakeholders to take it upon themselves to lay out a vision for a national cultural policy that promotes a democratic transition if there is no government with which to discuss the issue?

Moreover, what good would it do to envision the future of Syrian culture if the very future of Syria is uncertain? The world has helped bring about the main transformation of Syria’s unfolding rebellion: the transformation of its people from a people with a cause who can be leaders of change into the victims of a political and military conflict.

Furthermore, who has the right to coin a vision of the role that independent culture and creativity will play in making change happen in the Syria of today and tomorrow? At a time when no consensus exists on national priorities, today’s leaders are the objects of doubt. Though they are still there, the constants that underlie people’s affiliations are now the same constants attributed to supporters of several affiliations.

How can anyone envision a new structure for the official cultural sector at a time when Syria’s very future, at least its near future, remain open to all the possibilities? With this “explosion of possibilities”, one that is currently shaking all Arab societies, a question about the culture of crisis presents itself. A crisis creates its own culture. The culture of crisis is the historical end-result of the suffering of an entire stage of history, during which wars intermingle with civil wars, modernity with westernisation, and authenticity with Salafism (returning to the religious source). It causes a split between he who wields control, and those whom he has control over. And because it is thus, it is a stage in which beginnings are confounded with ends. In the culture of crisis are interwoven options and visions, some of which choose to flee, instead of facing the present, by seeking refuge in repeating old formulas, declaring irrationality and placing their fate in the hands of the unknown. They plunge us into the madness of kings’ sects and the wars of the sects’ kings, and turn in a vacuum. From there, we declare that things should continue to the bitter end, and that the fallen should continue to fall, and the compulsion to announce the death of the prevailing culture, the one that is incapable of maintaining control, is the only way to define the crisis and be able to say that this is not our crisis.”

In order to bring the dominant culture to an end, the independent Syrian cultural sector faces a responsibility that should not be delayed any longer. It starts with the creation of the sector itself, a sector that grew in the shadows as part of Syrian civil society, but without a voice, practices or foundation. It began to expand and seep into the empty small spaces with a flexibility that turned it into a liquid capable of seeping into any empty space hidden from light. This continued to happen after the revolution as the empty spaces only grew larger.

We are not trying in any way to define a vision (whether preliminary or final) of future changes in Syria’s cultural policies. Such a vision should be the collective outcome of stakeholders’ efforts to respond to a number of important questions, and arrive at a series of both intellectual and practical agreements. What we are proposing is the development of a vision of the main mechanisms, fields of activities and steps that should be pursued in order to reconsider the role, priorities and future visions of independent stakeholders.

Despite the apparent difficulties in garnering the opinion of intellectual stakeholders, and building a consensus on current and future priorities, 94% of the stakeholders that took part in the opinion survey on the priorities of cultural activities in Syria (initiated by Itijahat as part of the project “Towards a National Cultural Policy that Promotes a Democratic Transformation”), answered “Yes” to the question: Do you see any need for independent individuals and institutions to coordinate their work plans in the effort to formulate a parallel cultural policy that civil society’s stakeholders could adopt?

76% of those who took part in the survey said that in the short-term, work plans should be the outcome of collective thinking in response to direct and current requirements, while keeping the long-term in mind; i.e., planning for long-term change. On the other hand, 13% believed that the importance lies in long-term planning, while only 11% believed that the independent sector should formulate plans that lead to immediate changes.

The survey’s preliminary results show initial agreement on the need to coordinate efforts to reactivate the role of the cultural sector, which is currently facing challenges on several levels. The most serious among these could be the link with ongoing social activism, and culture’s ability to play a positive role at a time when sources of social division are multiplying.

General objectives of the desired cultural policy and the independent sector’s priorities

The current transformations are not only political in nature, but are also, at the core, a cultural transformation process. However, in light of the current radical changes unfolding in Syria, the country’s history in recent decades, the many priorities that fall on the shoulders of politicians in charge of the transition, and deeply entrenched mind-sets, we realise that, in the next stage of the country’s history, culture will not be a major preoccupation for the country’s decision-makers. This is why the responsibility for putting culture on the political discussion table falls on the shoulders of independent institutions, activists and researchers. The latter should ensure that cultural stakeholders take advantage of the process of reconfiguring Syria’s identity and personality to make culture an important component of the country’s transition, during the next stage.

The lack of specific suggestions regarding cultural activities in Syria necessarily signifies the inability to reconsider the specific structures, laws and work mechanisms. Thus replacing the current institutions would in fact simply be an echo of those that exist today. Not only does this mean the inability to enact free and democratic legislation that protects freedom of expression and promotes culture as a right for every citizen, it also means our inability as independents to become a genuine and effective pressure group.

There are four main avenues that could be developed as an initial step towards reconsidering the priorities of cultural activities:

1. A system of concepts and values;

2. The cultural stakeholders, who they are and what they do;

3. Monitoring and analysing current cultural policies;

4. The desired change in the relationship between government institutions and the independent sector.

We rely, in this context, on a series of priorities that together form a work plan, placing cultural activities on the table, using two parallel and complementary approaches.

The first approach involves responding to the immediate needs and requires quick action to promote culture as a principal player during the transitional stage. The second approach involves laying the foundations for a long-term change process directly linked to the impending political and social transformation.

1. A system of concepts and values

The need to reconsider various principles does not only rely on building consensus around them, but also on linking the theoretical and actual contexts within which they are used. This is especially true during a period of major change in the public’s perception of the significance of these principles, a time when these principles have become part of the battlefield, and a time when many of them are new to Syria’s cultural activism, at least at the direct and obvious level.

We will address here a group of principles used often over the past two years as part of theoretical studies and in the literature of cultural institutions and projects. We will also give examples of the major changes that have been introduced to them, since the onset of the revolution, in the following areas:

Identity, cultural, cultural interventions, cultural stakeholder, culture of coexistence, local societies, multi-party strategy, art, cultural diversity, cultural bridges, cultural reconciliation, cultural rescue, cultural services, sustainable development, cultural policies, transitional justice, civil society, the artist, diversity and identity, intercultural dialogue, cultural industries, cultural development, cultural decentralisation, communal peace, redress of grievances, dominance of the centre, creativity and organisation.

Some major concepts are at the foundation of cultural activism, such as “art”, “cultural stakeholder” and “cultural industries”, while others have gate-crashed the literature of culture, eliciting a variety of reactions from cultural stakeholders. While some see these gate-crashers as a vital necessity and a reaction to change, others see them as the intrusion of concepts and work mechanisms that do not really belong to the world of cultural activities, suggesting they have more to do with funding-related issues and, as such, are a threat to the creative process. Examples include “cultural reconciliation”, the “redress of grievances” and “dominance of the centre”.

Some of these concepts took on a different meaning in the Syrian context, including “cultural diversity”, which is undergoing a significant change in the ongoing process of exile. When we now say “cultural diversity in Syria”, we are no longer talking about diversity as a fact or a source of identity, but also as a source of conflict and struggle.

The same contextualisation applies to the cultural decentralisation that took place in Syria over the past two years and changed the country’s cultural geography; although this openness developed unplanned, it should be protected and built upon. This intrusion into the central infrastructure made us reconsider the relationship between art and society, since both the producer and the audience have changed completely. Before 2011, “the producer” was necessarily an artist or cultural stakeholder, in the technical sense of the term, regardless of the polemic that surrounds the concept of creativity as a profession in Syria and many other Arab countries, in the technical and economic sense of the term. The creative product had its own place and space, and these spaces had their own rules, customs and monitoring agencies. Bringing the product to the public sphere required endless negotiations, approvals and truces. One person or party possessed the moral authority to define what belonged to the creative sector and, as such, exhibited its product to the public.

After 2011, creative expression became an integral part of socio-political expression. Dozens of examples could be described, from banners held aloft to animated stories, caricatures, graffiti, sculptures, designs, films, videos, music and songs. Added to these examples are the modern forms of expression that can be linked to the effort to creatively own the public sphere, and thus symbolically to the difficulty of physically occupying the public sphere through demonstrations and sit-ins. One of the clearest expressions of this is the colouring of Damascus squares red.

On the other hand, the term “cultural decentralisation” is associated with various infrastructures, equilibriums and prerogatives of decision-making. The term first appeared in France in connection to budgetary allocations to various municipalities and governorates for cultural purposes. It actually means that the state allocates parts of its budget to the regions, and keeps a big part of it for items such as museums and public centres.

2. Cultural stakeholders

Understanding cultural stakeholders, who they are and what they do is one of the more important steps in the effort to develop a cultural vision for the future of Syria. Over the past two-and-the-half years, Syrian activism has produced a variety of cultural expressions that went well beyond the creative frameworks that existed prior to 2011. The cultural sector continued to produce works using a variety of forms and mechanisms. Some turned to political activism using a variety of tools and artistic expressions (music, drama, cinema and visual art) that focussed more on the political message than the artistic form or level and thus were, by definition, civilian activism. Others, however, tried to stay away from politics and the unfolding revolution, in particular those artists that were creative before the revolution and continued to be so afterwards, experimenting at different levels between the two political extremes.

While it was necessary before 2011 to decentralise culture by changing the planning mechanisms at the local and national levels, or planning to establish infrastructures away from the capital and other major cities, the revolution cast doubt on the monopoly of creativity by the centre thanks to direct action by new players who imposed themselves on the cultural map. The obsession with change was no longer a matter of laws and structures, but an acquired right that no one could deny.

These new players are individuals, groups and even societies that were once unconcerned with culture and art, but turned to creativity in the process of searching for their own discourse after the onset of the revolution in 2011. It is not enough to understand the dynamic that motivated such creativity in different societies, it is also necessary to have a more specific definition of those who stand behind it. The reason is that understanding the independent cultural sector after their emergence on the scene is very different from understanding what it was when it was still confined to leading individuals (artists) and groups (teams, institutions and troupes).

Will this decentralisation last or will political authority, regardless of its leanings, put its hand on culture once again? Will the new players be able to have an impact or has creativity, as an expression of participation in the process of change, lost the elements of sustainability? How could these individual initiatives be turned into pressure one could build on, especially in light of the new challenges embodies by the emerging religious and military forces that have become major players on the scene?

3. Monitoring and analysing current cultural policies

Studying the cultural policy of any country requires examination of major aspects of cultural activism, including organisational structures, decision-making and administrative mechanisms, cultural funding and legislation, the relationship between the public and private sectors, and foreign cultural relations.

However, despite what seems like a total absence of change in Syria in the cultural domain, as a result of the current situation, a close examination of the unfolding changes clearly shows that change at the cultural level (whether in the professional or communal, all-encompassing sense) reflects and will continue to reflect Syria’s fate.

A study of the main components of Syria’s current cultural policies will provide the debate with the essential keys to transition from the current condition to the desired condition. The change criteria for paving the way for a cultural policy that Syria’s cultural stakeholders can adopt will be determined against this background.

Based on a study of current conditions, we could closely examine the main focal points and criteria that need changing in today’s policies in order to adopt a new policy that promotes freedom of expression and creativity, and paves the way for the impending role of culture in the change process.

(Photo from the Festival’s website)

4. The desired change in the relationship between government institutions and the independent sector

A historical look at the development of cultural structures in Syria reveals an absence of effective and well-coordinated cultural policies, alongside a tendency to put ideology, propaganda and political mobilisation ahead of creative freedom and respect for cultural diversity.

Until March 2011, the Syrian state was in the process of openly transitioning from a centralised socialist system to one that relies on social market principles. The accompanying changes involving the expansion of the civil sector, as they called it then, and the strong emergence of the private sector. These changes helped the formation of independent cultural groups, which began to take their rightful place and space in the cultural sphere, emerging from under the cloak of official cultural discourse. This official discourse admitted that, to quote former culture minister Riad Nassan Agha, “culture should be a populist act rather than a governmental act”.

Today, in light of the radical changes in the conceptual, knowledge and value systems on which these political or cultural elites rely, there seems to be an urgent need to start rebuilding various cultural systems and infrastructures. There is also an urgent need to start laying the foundations for work, methodology, management, planning and organisational rules and regulations that promote the individual’s status, freedom and creative ability.

Despite all the changes that took place in Syria between 2001 and 2010, the official view of culture as a concept remains tied to the expected content of this culture, and the role it is supposed to play. At no time was there a cultural policy that openly recognised the need for liberation from the grip of the totalitarian, or dominant, culture or for relinquishing the notion of culture as a tool in the government’s hands.

What role should government institutions play in the promotion of culture and what kind of relationship should be built between the government and the civil sector?

From those who took part in the previously mentioned opinion survey, 55% focussed on the need for the official cultural institution to relinquish its ownership of cultural activities, their by-products and the cultural infrastructure, as a whole, in favour of playing the role of facilitator that allows for creative freedom and the freedom to practice. This could be done by laying the foundations for a legal system and infrastructures that allow cultural stakeholders to work in freedom, in an atmosphere that allows the independent sector to reclaim ownership of the cultural project.

Priorities of cultural activities in Syria:

The survey entitled “Priorities of Cultural Activities in Syria” posed a number of questions, for consultation purposes, about the current condition and future of cultural activities in Syria. While a number of questions focussed on the priorities and role of current independent cultural activities, one in particular asked the participants to list their priorities from the most to the least important. The preliminary results were as follows:

1. Use culture as a cornerstone for rebuilding communal peace;

2. Use culture to help address the psychological impact on various sectors of the population;

3. Culture is a tool to achieve the desired democratic transformation;

4. Culture should be an expression of the unfolding tragedy;

5. Culture should help protect material and non-material heritage;

6. Defending culture is every citizen’s right;

7. Culture should mitigate the impact of the newly emerged extremist religious forces in society;

8. Make culture part of relief efforts and the media;

9. Use culture as a factor of economic recovery.

The priorities revealed by the survey largely intersect with some of the key points in the list of “Priorities of Cultural Activities in Syria”:

Cultural change is the ultimate objective:

Syria’s social structure has been undergoing deep cultural changes since the beginning of the revolution in March 2011. The fact that economic, social and relief priorities are increasing ought to make long-term cultural change one of the most important preoccupations of independent stakeholders. As long as the desired change has to do with society’s culture, the “desired cultural change” will remain the compass, regardless of the variety of strategies and action mechanisms. The fields of action could be cultural, educational or relief oriented, with action perhaps even focussing on integrating different fields of activities.

Art is an aesthetic perspective against violence:

Anything that helps end the ongoing violence is a priority. Art, therefore, as a bright aesthetic perspective that helps mitigate people’s daily suffering, is a priority as well; it includes:

– Absorb violence and reduce the negative impact of sectarianism, thus helping avoid civil war;

– Art education: support artists through specialised art studies that allow them to help in the long term;

– Delineate a list of cultural stakeholders and learn about different gatherings and opportunities in which people could take part;

– Develop grants and support programmes for artists inside Syria;

– Support artistic work through critiques and writings. Put things in their context in a manner that accommodates modern art forms (graffiti, street art, etc.).

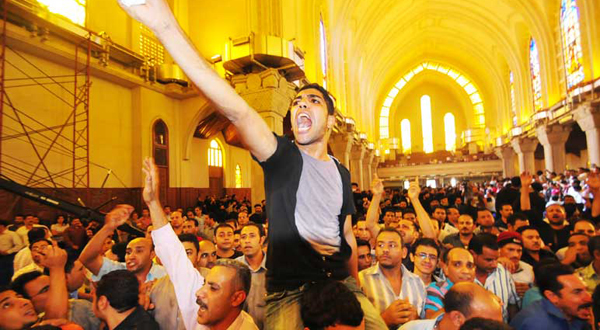

(AFP Photo)

The requirements: a comprehensive view with education as the cornerstone:

We should think about the complementary nature of various requirements and try to implement them. However, although many psycho-social activities are geared towards children, it is unacceptable that this be the only field of current activities. A very good example that helps us deal with the issue is the fact that Syria today has five different academic curricula: the National curriculum, the Kurdish curriculum, the Adjusted Libyan curriculum (UNESCO), the Turkish curriculum, and the Adjusted National curriculum. Another curriculum has recently been printed, the “Curriculum of the New Syrian Republic,” which involves three religious books (the Koran, Sunna and Fiqh [jurisprudence]).

If we adopt an open approach to culture, our field of activities becomes genuinely connected to society. Because education today is the foundation on which the new generation will be reared, we should focus on eliminating from it all preconceived and stereotypical notions that enshrine rejection of the other based on his or her affiliation.

Initial perspectives

Societies that have gone through a transition established social and cultural institutions that played a significant role in the process, with their ultimate objective being social cohesiveness and economic growth. And while cultural activism was the key work of these institutions, equality was the social glue. In these particular cases, cultural stakeholders were able to influence their societies in a variety of important fields, including economic revival and social cohesiveness, and managed to establish a dialogue between different societies, by approaching culture through two main avenues:

– Culture’s role in making reconciliation possible, with culture acting as both as a collective cure and avenue for interactive dialogue; and

— Culture’s role in fostering a democratic pluralistic society, in its capacity as bearer of citizens’ identity.

These earlier experiences elsewhere have shown that culture could offer a lot when given the chance. It could help bring views and opinions closer together, enshrine dialogue among different religions, promote understanding and reduce misunderstandings, and neutralise preconceptions and stereotypical images about the other.

So far, culture has been neglected as a basic factor of the conflict in Syria, its repercussions and resolution. There is therefore genuine need for a clearer understanding of what constitutes culture, and for adopting this understanding and making it part of more effective conflict resolution efforts.

Earlier experiences relied on various social change strategies by putting culture’s political, social and economic power to good use. Culture could be partly relied on to provide a conceptual framework for cultural interventions in the aftermath of political conflicts and armed struggles, interventions that could prove useful for both cultural stakeholders and policy-makers. We should also learn from available experiences about culture’s role in combating discrimination and alienation, to foster interaction in divided societies. To make this possible, we propose a series of specific programmes and work mechanisms aimed at changing policies in favour of promoting communal peace, based on the notion that art has the most advanced social healing abilities. We also need to place various communal peace plans in a more comprehensive context that involves building a consensual vision of Syria’s cultural policies, since “vision is the main motivator.”

The effort to develop a consensual vision of cultural policies rests on two different dimensions: the first relies on building consensus round the priorities of current, independent, cultural activities; the second is to start formulating the general avenues of Syria’s long-term cultural policies. By the priorities of current activities we mean those domains that culture’s independent stakeholders see as needing their urgent intervention. This involves evaluating the work that needs to be done according to these priorities and estimating their potential for success (i.e., the stakeholders’ ability to exert influence and bring about change). Although certain domains genuinely need urgent attention, they are beyond the independent cultural sector’s ability to act. However, instead of being a cause for concern, this should be a motivator and guide in determining the priorities of a strategy that would allow this sector to have a direct impact.

The fact that there are several controversial subjects in Syria today, like national identity, religion and political polarisation, does not mean that there are no common denominators. A good recommendation is to search for sources of inspiration and belonging deep within the hearts of the Syrian people today. It is not expected of the stakeholders to make everyone agree on a set of specific values; this is usually done to perpetuate the abuse of these values in time of conflict over wealth, power and cultural domination. What we are proposing instead is the development of programmes that give individuals and groups the opportunity to define and choose their identity and means of self-expression. We see culture as a constantly evolving product. The common denominator among successful experiences is not only finding opportunities for individuals and group to express their culture, but also providing these opportunities and guaranteeing the right to change and reproduce this culture.

If dialogue could be described as a bridge between cultures, then conflicts are the walls, whereby it is impossible to build bridges before destroying the walls. Transitional justice, accountability, constitutions and election systems are all about bringing down these walls.

Culture, however, takes a different approach; it seeks to climb up these walls rather than destroy them, see what lies behind them and rise above the ceiling. It does that for a very simple reason, namely its instinctive fear of seeing the accumulated mass of stones left by the destruction and not being able to wait until they are removed, until bridges are built and their resistance tested. Culture is therefore the safety valve for new construction projects. In no way do we support the reapplication of transitional programmes already tested in some countries which are based on turning the page on conflicts without studying and learning from them.

Instead, we strongly support implementing justice as part of the desired culture, to build Syria on strong legal, pluralistic and democratic foundations lest it remain subject to more strife and bloodshed. It is a culture that sees justice as applying the law to guilty individuals, but for groups it reserves only tolerance, forgiveness, acceptance and interaction.

Working on cultural policies involves consulting with others to build consensus among individuals, groups and institutions around the priorities of current cultural activities. The aim of this consensus-building exercise is to enlarge the role of culture as the bearer of change, with the independent cultural sector as its main motivator and, through that, to influence the unfolding events and prepare for the future. The work methodology essentially aims at allowing the largest number of independent stakeholders to express their views, make remarks, give advice and help make the decision. It departs from a major assumption that when culture seems the least important, it has a more immediate and effective role to play than in times of stability, whether real or not.

Based on the above discussion, below is a list of cultural work priorities, for responding to, the current changes and looking towards the future:

– To support art, its presence and its role as an aesthetic civil activity that preserves human values and promotes the Syrian people’s ability to envision the future. The prevailing discourse that says that culture and art are not a priority for governments and societies during periods of transition marginalises the important role of both civil society and society as a whole. Above all, art is a peaceful discourse that relies on the imagination and can envision the future directly or indirectly.

-To promote the presence of culture in Syrian societies and its role in bringing about reconciliation and communal peace;

– To focus on the role of culture in education, one of Syrian society’s most important present and future challenges. Integrating culture in the education process involves dealing with it in the broader sense of the term, including the concepts of identity and citizenship, alongside art, as tools of knowledge.

– To interact with the unfolding socio-cultural change, and direct it towards the promotion of a culture based on the varied and diverse elements underlying Syria’s cultural heritage.

– To focus efforts on laying the foundations of a cultural policy that guarantees freedoms of creativity and opinion, and that promotes culture as a basic right of the Syrian people. By cultural policy, we mean all the systems, legislation, organisational and institutional structures, and mechanisms that govern cultural activities in Syria.

To achieve these priorities, methodological work plans and specific measures should be developed based on a set of necessary strategies that enable the independent sector to play a direct and effective role.

These measures not only involve building and launching future work plans; they start by building the knowledge and capacity of the sector itself, forging alliances among its components, and designing work methodologies based on experiences that cultural stakeholders have themselves developed. Their departure point remains the re-assessment of the work culture that governs the sector’s mechanisms and general tendencies.

This piece was published on the Arab Reform Initiative website.

The Arab Reform Initiative was founded in 2005 by sixteen think tanks and research institutes from the Arab world, Europe and the United States. ARI is an independent research network with no ties to any specific country or any political agenda related to the region.

Since the founding in 2005, the ARI built a solid reputation in producing knowledge of the Arab region through in-depth research projects, engaging in collaborative work, building capacity of teams in different countries in data collection and survey research and developing a vast network of scholars, activists and practitioners who share the reform vision.