In order to discuss Al-Sisi’s relationship with politicians and get to the root causes of this apparent acrimony between the president and those working in politics in Egypt, we must review how the heads of the 1952 family changed their relationships with politicians and the political process, in order to understand the constants of the 1952 regime.

The 1952 regime transferred power from Muhammad Naguib to Gamal Abdel Nasser after scoring the last victory of the March crisis of 1954, which laid out, or more accurately, founded, some of the most important constants of the 1952 family as it later turned out. By this, we mean confiscating political life, a state monopoly on political work and its control of the public domain, granting space indirectly to the army in the public domain, and expanding use of security forces to control and manage all conflicts that may arise within the public sphere in general and the political sphere in particular.

Abdel Nasser’s regime extracted itself from the March 1954 crisis but remained weakened to some extent as a result due to a fluctuation in his image before public opinion. This was a natural result of the conflicts that broke out within the regime, but it came out victorious and unified, and more importantly, more palatable to the people. Why was this?

Because the people, in general, were fed-up with the slowdown in performance of the semi-democratic regime that laid the foundations for the 1919 revolution. The 1952 family deepened this weariness when it considered and then promoted, since its inception in 1952, allegations that democracy is only talk and inevitably leads to a waste of time and chaos. The democratic political process through which a competition is waged between parties divides the people and weakens the country, they said.

This process specifically is what has delayed Egypt in achieving any tangible achievements, which requires unification (to fight division) a system (to fight chaos) and work (to fight talk). This slogan was in fact chanted in the past, and we all heard these three words in a number of Egyptian films which decided to place the phrase in a number of clips and scenes unrelated to the sequence of events, confirming the filmmakers’ pride in Naguib’s visits to movie studies following the revolution.

President Naguib discussed this concept with them, and perhaps it would not be an exaggeration that the praise for the founder of this hymn has echoes that persist until now, and Al-Sisi’s supporters have the same degree of enthusiasm we witnessed in 1952 at the founding of the regime.

Nasser extracted himself from the crisis in March 1954 victorious, albeit weak to some extent, but his promises were soon matched with concrete achievements. This most notable of these included the agreement to evacuate British troops from the Suez Canal in 1954, and the Czech arms deal in 1955, with Nasser reaching the peak of his popularity by nationalising the Suez Canal in 1956.

In addition to these achievements, the fact that Muhammad Naguib and his “cavalry” did not form what seemed to be a coherent group or oligarchy that could form an obstacle to Nasser also helped the leader to secure his grip. His main rival, in fact, was the various political forces that ran the political process from 1919 through 1952. He was not posited against a group or particular direction, but he and the heads of the 1952 regime were instead posited against the political process of democracy itself.

A presence for politicians was not lacking, but Nasser and the other heads of the 1952 regime considered them to be employees of the state, or rather of the president, nothing more, because Nasser followed the political process closely. It was said that he participated in a limited way on the outskirts of the proceedings, and it was understood that the politicians at that time had visions and opinions as well as self-pride, which were very annoying to him.

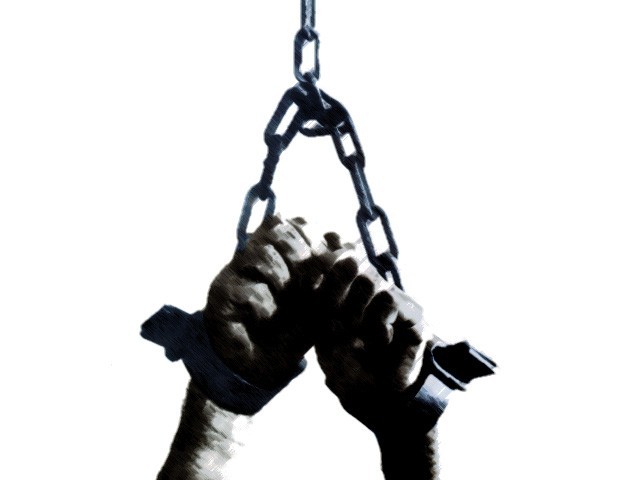

He wanted to make them forget and subjugate them before appointing them, and thus there was no negligence in Nasser torturing thousands of communists who supported him with all their strength. There was no answer to the question of the mystery that struck most of his advisors, communists among them, the question that looks for the reasons for which Abdel Nasser was pushed to torture communists.

I will describe to you a story recounted to me by my father. The events of this story took place in Orda Prison, a camp where Abdel Nasser tortured hundreds of communists in order to destroy their morale, not to obtain confessions. The story goes that at the peak of torture, one of the prisoners raised his head and said “Why are you doing this to us when I support and love Abdel Nasser?” The officer replied, as he continued to hit him, “so you’ll support him, not love him, you [expletive]” This is the message: You are an employee of a political department, body, or organisation which employs politicians to serve the state and support the state when required of you. Perhaps this explains the emergence of a means to express a subjugated opposition in Egyptian political literature.

Nasser succeeded, generally, in subjugating the political group, and he only did this through focusing on four main pillars: first, people’s weariness of the weak regime that governed Egypt from 1919-1952 and its slow performance. In my estimation, this weakness was a result of a number of considerations, the most important of which is that he was not able to take advantage of the change in the balance of international and regional powers that eventually formulated after the Second World War ended.

The second pillar was how Nasser succeeded in bringing together a large number of political groups with a socialist orientation with a permanent insistence on the distortion of politics, the political process, and democracy. The media, which he monopolised, confirmed that advocates for freedom were advocates for chaos and division and merely “all talk.” As a precautionary measure, the media added that these individuals could perhaps be agents of the US and the Soviet Union.

The third pillar was his success in subjecting politicians to the clout of his achievements, differentiated in terms of gender and class, and in terms of seriousness and feasibility as well, which he undertook from time to time, and perhaps because of this, he obtained more popular support. On the other hand, these achievements formed reason to support and praise him on part of politicians, as well as a means to justify practices and positions that may provoke resentment from the people.

The fourth pillar on which Nasser succeeded was ‘cracking the brains’ of the democratic opposition or political group, and through the word ‘cracking’ we are referring to detention and torture. In terms of what happened to the communists, we must also add that people like Louis Awad were arrested and tortured because they were communists! And the funniest and most tragic part was that the prisons were filled and for a few years with a few hundred of the detainees because they walked at the funeral of Nahas Pasha, chanting wholeheartedly, after all of Nasser’s ‘achievements’ the passage of 13 years since 1952, that Nahas was the nation’s leader.

Can we now, after discussing the performance of the 1952 family, understand the nature of the relationship between Al-Sisi and politicians? Or does the issue require us to review Sadat and Mubarak first in order to expose in some detail what distinguishes Al-Sisi’s position on the political process?! And to what extent are his constants consistent with that of the 1952 regime? How similar or different are the positions of all heads of the 1952 regime, and why?