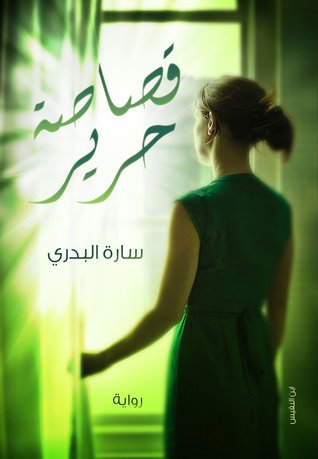

(Photo Handout from Sara Al-Badry)

By Rana Khaled

Believing that women can challenge society’s injustice and destroy all the restrictions, writer Sara Ali Al-Badry decided to pursue her dream of becoming a novelist. This came in spite of all the obstacles and constraints she’d encountered along the way. After getting her Bachelor’s degree in engineering, she decided to join the Faculty of Arts to study Arabic literature. Although many people discouraged her, she insisted on achieving the dream of her life.

In 2011, she published her first novel “Qosaset Hareer”, which attracted attention to the birth of one of the few knowledgeable female writers in Egypt. In 2012 she published her second novel, “Forbidden Fruit”, that provided insightful analysis for the Egyptian Revolution. After she gave birth to two children, Al-Badry realised that she can convey her beneficial experience to other mothers in her third book, “Mother on a Mission”, that was published in 2013. After one year, she published her fourth novel, “Hesn Al Shah”, in which she provided philosophical understandings for freedom and restrictions.

In an interview with Daily News Egypt, Al-Badry revealed secrets about her own life, the messages she wanted to convey through her novels and the moral restrictions she puts for herself while writing.

When did writing begin to dominate your life? And does this have anything to do with your childhood?

I was always drawn to writing and my childhood was full of signs that revealed the existence of such talent. The whole thing started when my teachers used to praise my Arabic composition in school. Then I started writing articles and novels, and allowed my mother and friends to read and discuss them with me. I clearly remember that one day I had an important Physics exam, while a very serious thought popped up in my mind and I stayed all the night trying to turn it into words to add to the novel I was writing. Writing is an important part of my life, I dream of every scene, of every idea and every character. I live with them and sometimes I just live their lives.

Why did you decide to start studying Arabic Literature at Cairo University after you got your Bachelor’s in Mechanical Engineering in 2001?

I decided to study Arabic literature after completing my engineering studies because I was madly in love with literature, and I decided not to get away from my first passion under any circumstances. My mother was so proud of this decision, although she felt pity for me because I had a job at that time and I had to exert a lot of effort. On the other side, my dad was completely against the whole idea, especially after I got married and he asked me many times to stop, but I couldn’t give up my dream. I insisted on it and this impressed my husband and his family who encouraged me a lot.

(Photo Handout from Sara Al-Badry)

What are the main messages you wanted to convey in your first novel “Qosaset Hareer” (“A Clip of Silk”)?

In each novel I write, there is always a main idea or objective that keeps pushing me. During the writing process, dozens of other ideas keep jumping up to my mind. In my first novel, the main idea was about the hidden war some people live through, although they don’t actually face it, nor do they have the required weapons to win. Each of us could be that person and every person around us can be that hidden enemy, even the closest ones. The novel contains some other ideas, like the unfair situations and circumstances the females in our society suffer from, and how most of us are just ignoring them because we’re more interested in judging how the woman acts or misacts.

In spite of the success your first novel “Qosaset Hareer” achieved, many people attacked the main character of your novel “Yosr” and the unrealistic idealism she portrayed. Others criticised the disintegration of the events, the absence of their logical sequence and the unjustified prolongation. How did you receive such critical views and how do you justify them?

It was my first time to realise how the same thing could be received with completely opposite opinions by different people. Some ladies sent me messages telling me “you were talking about me”. Many men said “Yosr is a traitor” while others said “she is too ideal to be true”. I kept telling them she is just a human being that seeks betterment, but she isn’t ideal. I believe that all of us had a conflict or a struggle around different issues. Some just chose to give up, some could stay longer and this is how I saw Yosr and wanted to convey her to the readers. As for the absence of the sequence or the illogical events, I actually have no answer for such criticism. Let’s say again that every reader has its own perspective and point of view. I do my best to develop myself each time, but I never aimed at satisfying everyone because it’s impossible.

Did you intend to insert the events of the revolution in your second novel “Forbidden Fruit”, as many young writers did to attract more readers?

Yes. It was so important to discuss revolution in my second novel, and I actually wonder why people criticised that. I believe it was a “must” to write about such a big event in my novel, as it’s my duty as a writer to write about important life incidents. Literature is a mirror of society, and writing is not only a hobby or a way to attract people. It is a treasure that you have to use to deliver something valuable to your audience. In this novel, I wanted to say how sometimes, a serious event could make us feel how weak and small our problems are. In a moment, a huge story of love and desire turned to be extremely small story compared to the future of a nation.

Why did you move from publishing novels about life, politics and society to writing the “Mother on a Mission” guide book that gives mothers instructions to follow from the first days of pregnancy until their children go to school? And what’s your source for such information?

This book isn’t only about advice, as it may appear, it talks more about the attitude of pregnant women and how they can be amused and responsible at the same time. I love this book more than my novels. I just realised that I have a good ability to analyse things, and I fortunately had a successful experience that I can write about in a simple way, so I told myself why not? I said if only one person made use of any word I wrote, I’ll be very satisfied and that’s why I plan to publish a second part, God willing.

(Photo Handout from Sara Al-Badry)

Why are you more oriented to present kinds of realistic literature in your novels? And do you intend to try any other genres in your upcoming literary works?

Let me answer the second part first. I always think about trying new literature genres. I can write short stories, critical articles or even stories for children. I even thought of writing a play. The whole issue is about time. As a working mother, I can say it’s too hard. Regarding the realistic fiction, I just love writing and reading about it. This type specifically can touch the reader deeply and affect his life in a way or another. It also lasts forever in the reader’s mind and soul. It can change lives.

In your last novel “Hesn Al Shah” (The Shah’s Fort), you presented different understandings for restrictions and freedom moving away from their superficial known meanings. How did the idea of this novel come up to your mind and why you pay special attention to the women in your novels?

In this novel, I wanted the reader to make sure that he is the one who can fight for his own freedom and choose his own way. Of course, I do care about women. Not just because I am a woman and I can tell a lot about them but also because I believe in woman’s great role and influence in society. I believe it is part of my duty to defend her against the injustice she encounters and convince men that they should exert more efforts to understand her way of thinking, her feelings and her needs. When they get that, they will own the whole world, in my opinion.

Because of the high moral restrictions you put in your writings, some people criticise that you prefer to stay away from presenting any models that may portray lust, homosexuality or psychological disorders although they exist in the real world. What’s your opinion on that?

Unfortunately, I’m supposed to defend myself now. But no I won’t. First of all, realism exists in all of my novels, and I always hear that from my audience. But let me ask: Do homosexuality or sexual deviation resemble the whole lives of the Egyptian people? I think the answer is “no”.

Secondly, I’ve already discussed some of these critical issues in my novels but in a descent and moral way. I believe that using “immoral descriptions” in literature is a very cheap and easy way some writers resort to, whether to win more audience or to free their energy under the claims of freedom of expression. Acting responsibly pushes you to think well about how you are going to make others think, or even live. This is literature for me, extremely effective. Can build or destroy a nation.

(Photo Handout from Sara Al-Badry)

Who are your favourite writers?

From the leading writers’ generation, I can pick Yousuf Edrees, Nageeb Mahfouz, Ehsan Abdelkoddos. I also love Bahaa Taher, Galal Ameen, Rabeia Gaber, and Ibrahim Abdelmageed and many others.

Have you received any offers to turn your novels into films or plays? And what about your upcoming projects and literary works?

No, I never received such offers, but let’s agree that it will not be literature, it is a different type of drama, because cinema has its different aspects and tools. Regarding my coming works, I have a lot of ideas in my mind but I still can’t decide which one will be the next. Just wish me luck.